What is the "Jock Tax"?

The commonly labeled “jock tax” is not a new tax but simply the focused enforcement of state income taxation on a particular demographic of individuals – professional athletes. These state tax principles are applicable to any employee who travels to another state for part of their employment. However, the label has been created because professional athletes are the most recognizable class to be subjected to such a drastic increase in enforcement.

History

The first mention of states specifically enforcing tax law on professional athletes was found in an appeal brought before the State Board of Equalization of the State of California for 1968 taxes owed by a San Diego Charger who was not a resident (i.e. a nonresident taxpayer) of California.[1] The dispute related to how much income a state could claim to be earned in their state by a nonresident professional athlete who played games in their state. The California State Board of Equalization ruled California could apportion the percentage of Mr. Partee’s “working days” that were spent in California to Mr. Partee’s annual salary and tax that income accordingly.

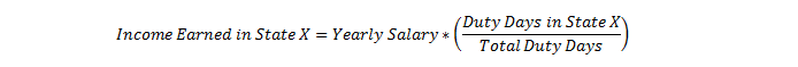

Restated, California could tax Mr. Partee on the percentage of the income he “earned” in California which is calculated by [(Working Days in California)/(Total Working Days)] * Annual Income.

This appeal brought the first mention of an apportionment method being applied to nonresident professional athletes.

The more publicized beginning of the “jock tax” is referred to as "Michael Jordan’s Revenge". This version of the “jock tax” history states the “jock tax” debuted in California in 1991. The story continues that California, upset their Los Angeles Lakers had just lost the NBA finals (4-1) to the Chicago Bulls, decided to levy state income tax against the salary earned in California that year by Michael Jordan and his teammates. Infuriated that California had begun taxing Illinois' hero, the Illinois legislature responded by passing their own “jock tax” law which taxed visiting professional athletes. Illinois’ law didn't tax all professional athletes but only those who played for a team whose home state taxed visiting athletes. Thus, began “Michael Jordan’s Revenge”.

While the above story accurately depicts Illinois Senator John Cullerton’s creation of a retaliatory bill implementing Illinois “jock tax”, it inaccurately describes the history of how the overall “jock tax” began. As previously mentioned, California began enforcing their taxation of nonresident professional athletes 30 years prior and many other states had begun the same practice shortly thereafter. New York made their own judicial rulings on the taxation of professional athletes in 1979 and 1982. Wisconsin had also ruled on a dispute regarding the taxation of professional athletes in 1989. At least these three states had begun taxing nonresident professional athletes before the well-publicized version of the “jock tax” history “began”.

Since the increased awareness Illinois brought to the idea of states assessing taxes specifically to professional athletes, every state with an income tax that hosts a MLB, NBA, or NFL team has implemented some form of a “jock tax”. This is not surprising as states are constantly looking for revenue and wealthy individuals who are forced to work in your state but unable to vote for or against your laws are easy targets. This has turned into quite a revenue stream for states. California received $171.7 million in tax revenue solely from professional athletes in 2010.

History

The first mention of states specifically enforcing tax law on professional athletes was found in an appeal brought before the State Board of Equalization of the State of California for 1968 taxes owed by a San Diego Charger who was not a resident (i.e. a nonresident taxpayer) of California.[1] The dispute related to how much income a state could claim to be earned in their state by a nonresident professional athlete who played games in their state. The California State Board of Equalization ruled California could apportion the percentage of Mr. Partee’s “working days” that were spent in California to Mr. Partee’s annual salary and tax that income accordingly.

Restated, California could tax Mr. Partee on the percentage of the income he “earned” in California which is calculated by [(Working Days in California)/(Total Working Days)] * Annual Income.

This appeal brought the first mention of an apportionment method being applied to nonresident professional athletes.

The more publicized beginning of the “jock tax” is referred to as "Michael Jordan’s Revenge". This version of the “jock tax” history states the “jock tax” debuted in California in 1991. The story continues that California, upset their Los Angeles Lakers had just lost the NBA finals (4-1) to the Chicago Bulls, decided to levy state income tax against the salary earned in California that year by Michael Jordan and his teammates. Infuriated that California had begun taxing Illinois' hero, the Illinois legislature responded by passing their own “jock tax” law which taxed visiting professional athletes. Illinois’ law didn't tax all professional athletes but only those who played for a team whose home state taxed visiting athletes. Thus, began “Michael Jordan’s Revenge”.

While the above story accurately depicts Illinois Senator John Cullerton’s creation of a retaliatory bill implementing Illinois “jock tax”, it inaccurately describes the history of how the overall “jock tax” began. As previously mentioned, California began enforcing their taxation of nonresident professional athletes 30 years prior and many other states had begun the same practice shortly thereafter. New York made their own judicial rulings on the taxation of professional athletes in 1979 and 1982. Wisconsin had also ruled on a dispute regarding the taxation of professional athletes in 1989. At least these three states had begun taxing nonresident professional athletes before the well-publicized version of the “jock tax” history “began”.

Since the increased awareness Illinois brought to the idea of states assessing taxes specifically to professional athletes, every state with an income tax that hosts a MLB, NBA, or NFL team has implemented some form of a “jock tax”. This is not surprising as states are constantly looking for revenue and wealthy individuals who are forced to work in your state but unable to vote for or against your laws are easy targets. This has turned into quite a revenue stream for states. California received $171.7 million in tax revenue solely from professional athletes in 2010.

Overview

Like all US citizens, professional athletes must pay both federal and state income taxes. However, under the “jock tax” detailed above, professional athletes pay state income tax in each state they play. The legal theory is that you are required to pay state income taxes in the state you earn that income and thus the professional athletes earn income in the stadiums they play in each season. But how much income does an athlete “earn” in each state? Does a player earn their money only by playing games or do they earn their money when practicing, making media appearances, off-season workouts, etc.?

To solve this problem, states have generally adopted what is known as the “duty day” method to calculate how much income athletes earn in their state. This method is generally calculated as the percentage of duty days spent in the respective state, compared to the total duty days that athlete had that tax year, multiplied by the player’s salary.

Like all US citizens, professional athletes must pay both federal and state income taxes. However, under the “jock tax” detailed above, professional athletes pay state income tax in each state they play. The legal theory is that you are required to pay state income taxes in the state you earn that income and thus the professional athletes earn income in the stadiums they play in each season. But how much income does an athlete “earn” in each state? Does a player earn their money only by playing games or do they earn their money when practicing, making media appearances, off-season workouts, etc.?

To solve this problem, states have generally adopted what is known as the “duty day” method to calculate how much income athletes earn in their state. This method is generally calculated as the percentage of duty days spent in the respective state, compared to the total duty days that athlete had that tax year, multiplied by the player’s salary.

In addition to the tax owed to each state where a professional athlete plays, a professional athlete (as is customary with any taxpayer) is taxed on their entire annual income in the state they are a resident. This is why it can be important for professional athletes to reside in a state that has very low, if any, state income taxes.

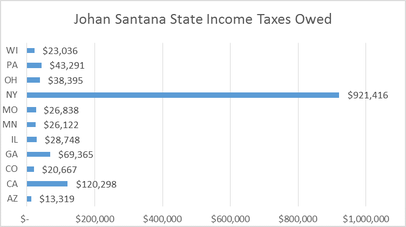

For example, consider the estimate in state taxes former NY Mets Pitcher Johan Santana owed to the various states where he played last year. Assuming the best case scenario that Johan was a resident of a state that did not have a state income tax[2], he would have still owed $1.33MM in state income taxes last year. Had Santana also been considered a resident of New York, that would have been an extra $1.24MM tax bill owed to the state of New York! Below is a chart of the amount of state income taxes Santana would have paid to each state he played in last year if he were not a resident of New York.

|

You can read more examples of the "jock tax" here.

Sources

- In the Matter of the Appeal of DENNIS F. AND NANCY PARTEE, 1976 Cal. Tax LEXIS 35

- Players do not have to be residents in the state their team resides

- For more information on the history of the Jock Tax read "When is a CPA as Important as Your ERA? A Comprehensive Evaluation and Examination of State Tax Issues on Professional Athletes" by Alan Pogroszewski